There is a wide range of whiplash symptoms. The most common, of course, are neck pain and headache, but a substantial percentage of patients report other, more difficult to understand problems as well. Some of these symptoms include dizziness; problems with balance; difficulties with attention and concentration; and sleep disturbances.

A number of theories have been put forth to explain these myriad symptoms. Some researchers have suggested that brain injury is responsible, while the insurance industry insists that these symptoms are fabricated.

A recent study1 from Sweden attempts to answer some of these questions by examining the functions of the brain in whiplash patients.

The study started with 40 patients with grades II and III whiplash injuries. The patients were given neuro-otological tests within two months of the injury and again two years later. These tests included auditory brainstem response tests (ABR) and oculomotor function tests, including evaluation of saccades (the rapid, step-like voluntary motion of the eyes used when reading or scanning an image).

ABR tests involve measuring the patient’s neurological response to a repetitive sound stimulus:

“A brief sound causes a series of electrical waves, in the nanovolt range, that can be recorded from the surface of the head. The signals are so small that they are normally buried in background electrical noise, but when the same brief stimulus is presented many times and the responses are averaged, the waves can be measured reproducibly. Early peaks in the waveform represent electrical activity in the eighth nerve arriving at the cochlear nuclei, and later peaks represent combined activity at successive sites in the auditory pathway.” 2

By analyzing the waveform, it is possible to identify dysfunction along the neurological pathway.

Results

At the two-year follow-up, 16 of the patients (40%) had no symptoms from the original injury. Ten patients (25%) complained of intermittent neck pain, headache, and radiating pain in one or both arms. Four patients (10%) also reported memory impairment, concentration problems, and showed neurological deficits. Another 4 patients (10%) were still on sick leave.

In the smooth pursuit tests, 5 patients showed abnormalities in the first test. Three of these patients improved, but two showed worse results at the two-year follow-up. These two patients who worsened over time also showed problems with their ABR tests.

Ten patients showed a worsened score on saccade velocity at the two-year follow-up.

What is at the root of the chronic pain and the neuro-otological signs? The authors suggest two possible explanations: altered neurological responses of the brainstem, and direct trauma to the brainstem.

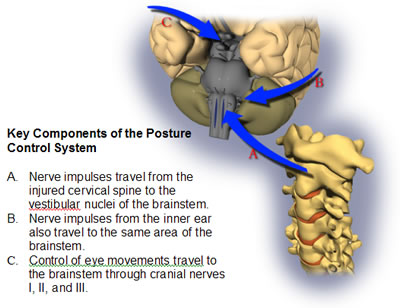

The first explanation would describe the symptoms of most chronic whiplash patients and works as follows: The cervical spine plays a key role in how the brain maintains balance, and signals from the injured cervical spine travel through the spinal core to the brainstem—specifically the vestibular and oculomotor nuclei. This is the same part of the brain that receives the signals from the inner ear, via the eighth cervical nerve. A painful neck can cause overexcitation of the nerve pathways, resulting in altered functioning of the brainstem. These alterations in the brainstem can in turn cause dysfunction in eye motility and balance, since these different systems all work together as the Posture Control System.

Most patients with chronic whiplash pain and ocular and auditory signs would fit in this category. However, this mechanism may not account for those patients with the most severe symptoms: “In the present study, we found two patients with pronounced pursuit abnormalities compatible with organic brain/brainstem lesions.”

So, according to this small study, about 2% of whiplash patients have signs of brainstem damage. This may seem like an insignificant number, but when we consider that there are approximately 1 million whiplash injuries in the US each year, there may be 20,000 cases of brainstem injury from auto collisions annually.

This study provides two important pieces of information about chronic whiplash: the first is that ABR and saccade tests are an objective way to measure altered neurology in these patients; the second is that some patients may have actual brain injury from these collisions.

For patients with more severe symptoms, it may be advisable to have them evaluated for saccade movements and ABR by an audiologist.

- Wenngren BI, Pettersson K, Lowenhielm G, Hildingsson C. Eye motility and auditory brainstem response dysfunction after whiplash injury. Acta Otolaryngologica 2002;122:276-283.

- Nolte J. The Human Brain: An Introduction to Its Functional Anatomy. 2002, Mosby, p. 355.